Warm blooded turtles?

If you entered this post to comment the error in the title, then I have one word for you.

Gotcha!

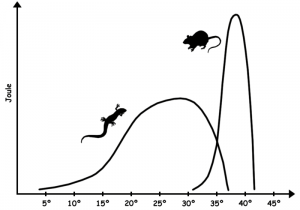

Yes, “warm blooded” animals are not, really, warm blooded. After all, a lizard in the baking sun has a core temperature higher than most mammals, but it is still called “cold blooded”. So-called cold blooded animals cannot regulate their body temperature, and rely on external heat sources. So they are usually term ectothermic (externally heated/cooled) as opposed to mammals and birds which are endothermic (internally heated/cooled). Actually many ectotherms are also poikilotherms: their body temperature varies across a large temperature range. This is opposed to mammals, which are homeotherms: their effective body temperature range is much narrower: humans die at anything above 43C or below 32C.

Sustained energy output (Joule) of a poikilotherme (a lizard) and a homeotherm (a mouse) as a function of core body temperature. The homeotherm has a much higher output, but can only function over a very narrow range of body temperatures. Credit: Petter Bøckman Wikimedia Commons

So what’s this about warm-blooded turtles? The answer lies with a long-standing puzzle posed by Leatherback turtles. Leatherbacks are large sea turtles that are found in very diverse environments, from the tropics to the arctic and antarctic. We are talking about a single species, not a family or even genus. And by the way, for a 900kg turtle, a leatherback can sure move: leatehrbacks have been clocked swimming at 36 km/h; I got a traffic ticket for less once.

This fast and furious turtle also has a core temperature that is quite high, and is more-or-less steadily maintained in the freezing arctic and in the balmy tropics. The long-standing question is: does a leatherback maintain its temperature through behavior (like a lizard which goes underground when it is too hot, and sits in the sun to warm itself in the morning), or does it have a set of of internal temperature control mechanism, like mammals and birds? Note that a lizard, being ectothermic, can operate over a larger range of internal temperatures than, say, a mouse (or human).

Well, the leatherback does have something internally, but not a mammalian mechanism. Rather, what it has is large body mass: 900kg, so its surface-to-volume ratio is much lower than that of smaller animals. As a result, the leatherback loses less heat to its surroundings, and maintains a higher core temperature than smaller sized ectotherms. But what about cooling off? Well, leatherbacks have been shown to have pink skin sometimes: so they might be using extra blood flow to the surface to cool off. In 1990 Paladino, O’Connor & Spotila have suggested a new temperature control mechanism they called gigantothermy: controlling core temperature by virtue of a large body size. Using size vs. shape equations (and assuming a cylindrical turtle), they have shown that large ectotherms can minimize heat loss, and that blood flow to the surface may account for a heat loss mechanism. They even went as far to suggest that large dinosaurs adapted do a large variety of climates by virtue of gigantothermy. So unlike lizards which are ectothermic and poikilothermic, they suggested that the leatherback is ectothermic , but homeothermic.

However, a study published in PLoS-ONE last week argues that leatherbacks are, in fact, endothermic. A group of scientists from Canada, the US and the British Virgin Islands studied two juvenile leatherbacks in water tanks. One weighing 16kg and the other 37kg. When cooling the tanks, they saw that both turtles maintained a core temperature higher than the water’s,

![]()

but the larger turtle maintained a larger difference between its core temperature and the water temperature. So size does matter… in helping maintain a constant temperature. The turtles activity also increased as the temperature was lowered: so they were basically moving around to keep warm. Those were young turtles, so the temperatures ranged between 19C and 31C. The assumption is that as the turtles mature and grown larger, their body size adds to their adaptive range, so that the 900kg version can swim in the arctic as well as at the equator.

In high water temperatures, the turtles showed decreased activity: kinda laying around, not doing much, chillin’, having a frozen margarita. But they also lost more heat through their shell & flippers. So a mix of behavioral and internal control. The picture is that leatherbacks are, therefore endothermic and homeothermic, although not that good at it: they control their core temperature using metabolism, and are much better at it than a lizard, but not as good as a mouse. So there is an evolutionary aspect to this too: leatherbacks demonstrate how some animals may have moved from ectotermy to endothermy.

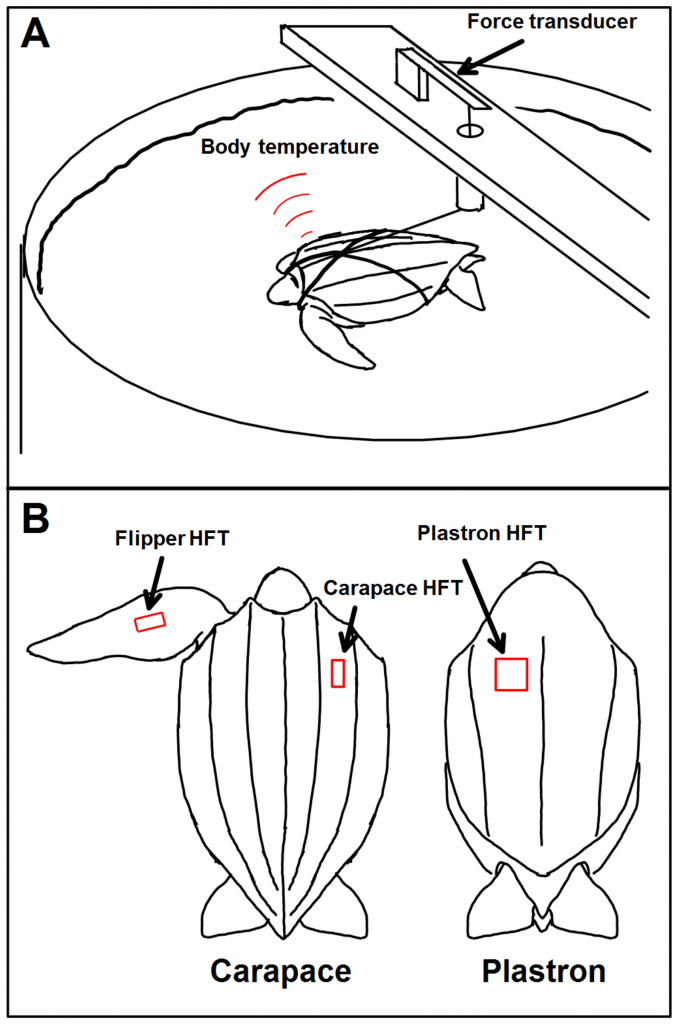

Finally, the cool, geeky bit: to constantly measure the turtles’ core temperature over time, the scientists had them swallow a miniature thermometer that broadcast its temperature. To measure heat flux (heat loss to the environment), they attached heat sensors to the turtles using superglue. The sensors were wired outside the tank (no WiFi sensors for those sensors, I guess). To measure activity, the turtles were tethered to a motion transducer.

(A) An illustration of the turtles harnessed in their tanks. (B) The placement of the heat flux transducers (HFT) on the animals. From: Bostrom BL, Jones TT, Hastings M, Jones DR (2010) Behaviour and Physiology: The Thermal Strategy of Leatherback Turtles. PLoS ONE 5(11): e13925

Bostrom, B., Jones, T., Hastings, M., & Jones, D. (2010). Behaviour and Physiology: The Thermal Strategy of Leatherback Turtles PLoS ONE, 5 (11) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013925

Paladino, F., O’Connor, M., & Spotila, J. (1990). Metabolism of leatherback turtles, gigantothermy, and thermoregulation of dinosaurs Nature, 344 (6269), 858-860 DOI: 10.1038/344858a0

Cool post! I don’t like ‘cold blooded’ and you made a good job explaining the terminology. I believe tuna are also endotherms.