Distant homology and being a little pregnant

(Thanks to F.B. for the inspiration).

Sigh… people don’t seem to learn. It’s been almost 22 years (yikes!) since a distinguished group of scientists published a letter in Cell calling for a responsible use of the word “homology”. If you were born when that letter was published, then in the US you can already drink legally. And you may very well want to, by the time you finish reading this post.

As of today there are one hundred and sixty seven articles listed in PubMed with the phrases “distant homology” or “remote homology” in either the title or the abstract.

Please: make it stop.

Homology is a qualitative term. It means having a common evolutionary origin. Two genes / proteins / organs are either homologous, or they are not. They cannot be “somewhat homologous” or “partially homologous” or (a favorite among molecular and structural biologists) “distantly / remotely homologous”.

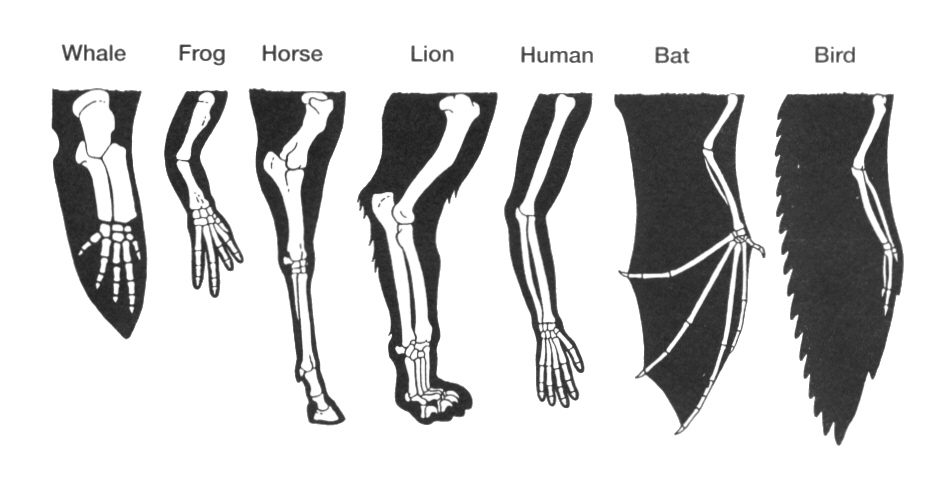

Homology is inferred from similarity. Similarity is quantitative. If organs are sufficiently similar, like mammalian forelimbs, then they are considered to be homologous. They maybe more similar (like the hands of humans and chimpanzees), or less similar (like human hand and a bat wing). Nevertheless, once they pass a certain similarity threshold, homology is inferred. The same applies to sequences of proteins and nucleic acids. Similarity can be measured. Different degrees of similarities can be compared and scaled.

If two protein sequences are aligned, and 40% of the amino acids in the alignment are identical, then the two sequences have a 40% identity. The do not have a 40% homology. They are homologous, and the homology is inferred from the similarity. We observe that the two sequences are similar, and then we conclude that they are homologous. We use the sequence similarity, as measured by percent identity, to trace a line of common descent for those proteins we deem homologous.

(As an aside I should say that the percentage of sequence identity, or %ID is not a very good measure for inferring homology, nor is it for measuring similarity. It is an easy one to use: but it is very coarse and prone to errors. There are many better measures out there, including statistical ones like e-values, p-values or information theoretic ones like bit scores. But I digress, and this is a matter for another post.)

But once we confuse observations with conclusions, things quickly become an impossible muddle.

Am I not not just picking nits here? I mean, surely when the term “distant homology” comes up in a paper or in conversation, we all know the meaning. Distant homology means having a common evolutionary origin, but with a common ancestor that was around a long time ago. “Distant homology” is intuitive, brief yet understandable. it is less cumbersome than: “homologous, with a distant common ancestor, as concluded form a low yet statistically significant similarity” which is what we really should say if we properly separate observations from conclusions, as captain nitpick would have us do.

Allow me to answer with two examples. First, I have read several papers discussing “structural homology” in the context of protein structure. Those papers that discuss structural homology were actually using a verbal shortcut for a homology inferred from structural similarity. That is, they inferred common descent from protein structural similarity. This kind of inference is highly contentious, and while not necessarily wrong, must be done with great care and proper caveats. However, once the researchers rolled up observations with conclusions by using the “structural homology” verbal shortcut, they absolved themselves from convincing the reader that structural similarity is indeed a good measure of homology, and jumped directly to the conclusion that there is indeed an homology here. The framework for inferring homology from sequence similarity is well worked out, but not so for structure, yet. Therefore, even if we do use the verbal shortcut “distant homology”, we can only use it by virtue of having a certain measure of similarity well-established already, as in sequence based similarity. If it is not well established, and in using structural similarities, we fail to go through the proper scientific channels that consist of providing convincing observations prior to providing conclusions.

Second: even worse is the use of the term “functional homology”. This is a clear case of the word homology used as a drop-in synonym for similarity. The misnomer “functional homology” is typically used in studies where proteins that are clearly not homologous perform similar functions. Why infer evolutionary descent when clearly that was not intended in the first place? Well, once you start confusing similarity with homology, observations with conclusions, and make them synonymous, this is what happens.

So don’t even start this confusion. Separate observations from conclusions, and make the former support the latter. Homology is qualitative, similarity is quantitative. Genes cannot be distantly homologous any more than a woman can be a little pregnant.

Now you can have that drink. Unless you are a little pregnant.

Gerald R. Reeck, Christoph de Haëna, David C. Teller, Russell F. Doolittle, Walter M. Fitch, Richard E. Dickerson, Pierre Chambon, Andrew D. McLachlan, Emanuel Margoliash, Thomas H. Jukes and Emile Zuckerkandl (1987). “Homology” in proteins and nucleic acids: A terminology muddle and a way out of it Cell, 50 (5) DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90322-9

You missed out the horrid term “micro-homology” – possibly meaning just two basepairs that happen to be identical at either end of a CNV or repair event. They really mean micro-identity. I might have a macro-drink…

@Ben Blackburne

I never heard of micro homology, and judging by your description, I probably should be happy I did not. However, now that you mentioned it, I am compelled to look it up.

What about if you have some sort of chimaeric protein, with one domain homologous with the other protein in question while the other is not? Would those proteins still be homologous, or would partial homology actual be a sort of valid term there? Or is it best to simply specify the domain?

Just curious… we do developmental/cell biology here, so we’re kind of expected to butcher anything evolution-related beyond all possible recognition =P

Cheers,

-Psi-

If you’re defining homology as having a common evolutionary origin, don’t a hell of a lot of things have this, if you look back far enough?

Is there little/more/lot usage, a shortcut to indicate how far they have to go back to find a common evolutionary origin for those two things being compared? (on top of other differences).

You just made me change the term “remote homologs” that I’ve used once in a paper, not in the title or abstract. I’m now using “divergent sequences” (I hope that’s better…). Phew. That could’ve been embarrassing. Now I just have to worry about the rest of the content. At least I’m not using “percent homology” anywhere.

I greatly appreciate this post, as I’ve railed against the use of homology to mean “similar” many times. But might be a lost cause. We might have to live with homology having different uses in molecular biology and evolutionary biology. Having a word having two meanings is a problem, it isn’t a horrible problem. We cope with “nucleus” meaning both a eukaryotic organelle and a cluster of protons and neutrons, after all.

@Psi Wavefunction

Since you specifically asked about a chimera, then the answer is already contained in your question. A chimera would be composed of two distinct sequences fused together artificially. So if you have protein A homologous to A’, and a chimera composed of two domains A’+B, it’s fairly tautological.

I assume though, that you were referring to natural gene fusions that happen throughout evolutionary time. The answer is the same is the chimera. The evolutionary “quantal units” so to speak are the protein domains. Just like we look for homology between organs (e.g. limbs) when we compare animals.

Well, if we go back far enough, all organisms are descended from LUCA, the last universal common ancestor some 2.5 Billion (American Billion: 10^9) years ago.

But the term “homology” does not apply to whole organisms, but rather to defined parts of organisms, or, in molecular biology, to proteins and genes. Let’s take wings for example: bat wings and human arms are homologous: they both diverged from the forelimb of the common ancestor of bats and humans, some 600 million years ago. But bat wings and insect wings are not homologous, even though they are both used for flying. Bat wings are adapted forelimbs, whereas insect wings are adapted exoskeletal outgrowths.

A molecular example: one of the early enzymes in the NAD synthesis pathway is L-aspartate oxidase. This is true for most animals, plants, and bacteria. However, in some bacteria and in archaea, L-aspartate oxidase does not exist in the genome, though it catalyzes a necessary step in a vital pathweay. Instead, we find L-aspartate dehydrogenase, which is completely differnt in structure and sequecne form L-aspartate oxidase, and also differnt in the biochemical functionality. But as far as physiological functionality is concerned, it serves as a non-homologous replacement to L-aspartate oxidase. Again, no homology here.

So no, not everything is descended form the same common ancestry if we look far enough. New genes and functions crop up regularly in evolutionary time.

Ha! I just updated the post to include “remote homology”. Thanks for the reminder. The PubMed dragnet nabbed 100 additional offenders, some of them good (soon to be ex) friends of mine.

The verbal shortcut is awfully easy route to take. The problem is that, in the long run, it creates more problems than it solves. A bit like the Dark Side of the Force.

The two different meanings of nucleus are used in rather different context, and it is hard to imagine them being confused with each other. On the other hand, homology is used in evolutionary biology, and in molecular biology when discussing evolutionary theory, which can be confusing. Hey, percent homology has been practically eradicated (though not quite). So there’s hope yet.

Ah, one of my pet peeves as well 🙂

Just last week I rejected a paper that confused similarity with homology. That wasn’t the main reason for the rejection – there were plenty of other problems with the paper, plenty of which were confusion with terms – but it did add to it.

I applaud the post.

A minor observation about “remote homologs” – often people use this term to denote a difficulty in detecting the (true) homology between 2 proteins that share a low sequence identity, rather than “quantifying” homology. I believe this is the way the term has often been used in the structure prediction field (esp. CASP). IMO, not as bad as “distant homology”. But admittedly, it’s a slippery slope…

Hi

Think this is really good question. From one side, homologues mean the same as relatives, so we know phrase “distant relatives” or “close relatives”.

At the same time we can’t to say(?), that all ppl have one common ancestral pra-pra-…grandma&grandpa, may be it was in different places

and in different times with different individuals, and it means that may not all the ppl are relatives. But we have common results – Homo sapiens.

From this point of view, we just have a set of properties, which define a species.

In case of proteins we have the close situation – may be on prebiotic phase of evolution in the Earth, there are a lot of places, where first protein-like

sequences were organized. So we just have a set of properties which define proteins and it means that as ancestor we just have some kind of processes.

From my point of view we can to say “distant homology proteins” if we have a strong results about a process of there divergence, otherwise

we can speculate about it only. As a measure of homology it’s possible to use a set of parameters which define a divergence process.

So the question is in the relationship of cause and effect and not in terminology.

agree with wiki : ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homology_(biology) )

“The phrase “percent homology” is sometimes used but is incorrect. “Percent identity” or “percent similarity” should be used to quantify the similarity between the biomolecule sequences. For two naturally occurring sequences, percent identity is a factual measurement, whereas homology is a hypothesis supported by evidence.”

thanx