The Inside Poop

It’s pretty much common knowledge that mother’s milk is the healthiest food for infants, and that it bestows health benefits upon mother and baby that formula feeding cannot match. The unique combination of lipids, sugars, proteins and antibodies is not even close to being rivaled by baby formula manufacturers. With few exceptions, such as when there is a concern that the mother is contagious and may infect the baby, breastmilk is the recommended diet for infants.

As I am interested in things microbiological, I have been especially interested in the effect of breastmilk on the baby gut and gut microbiota. There have actually been quite a few studies on that, but most of these studies were about the gut microbiota only. However, we can’t really separate our gut from the microbes that reside in it. The bacteria in the human gut affect the gut (and, in turn, the entire body) and are affected by it. The gut is really a superorgan, composed of a minority of human cells, and 1014 bacterial cells. Most of the gut is actually bacteria, not human, but the part that is human is important, since, well, it’s “us”. (Well, kinda hard to tell now which “us” is “us” and which “us” is “the bacteria that live in us”.) To understand what goes on there we need to study both bacterial and human cells. While adult microbiota+gut systems have been studied, mostly for the effect of probiotics, there have not been studies of baby guts because you cannot perform consented invasive procedures on babies. In other words, you cannot scrape their colons for gut lining, or epithelial, cells. So there has not been much of an opportunity to study the gut epithelium+microbiome in human infants.

The opportunity came with Robert (“Robb”) Chapkin from Texas A&M University, and Sharon Donovan from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Robb has developed a system to isolate gut epithelial cells from the feces. We shed about millions of cells from our gut when we defecate, and Robb’s lab has a way to fish those gut lining cells out of the stool. Thus, we can sequence the mRNA, and find out which genes are transcribed in the baby gut. At the same time, we can analyze the baby’s microbiome. Enter Sharon Donovan’s lab, who has studied 12 babies, six were breast fed and six were formula fed.

This is where Robb contacted me, and generously invited me to College Station, Texas about a year and a half ago. Aside from enjoying Texan hospitality (big steaks) and meeting people, Robb brought me into this fascinating study. They needed a bionformatician to help analyze the gut transcriptome and gut metagenome data. I am very glad they contacted me, since this started a very enjoyable collaboration and a scientific journey whose results are published this week in Genome Biology. I was put in touch with two great statisticians, Ivan Ivanov and Scott Schwartz, also at Texas A&M. We put our heads together, and came up with a strategy.

Analysis flowchart. Reproduced from Genome Biology 2012, 13:R32 doi:10.1186/gb-2012-13-4-r32 under BMC CC2.0 license. Click to enlarge.

First, we analyzed the microbiome data, using several standard pipelines, like MG-RAST for function analysis (thanks to the folks at Argonne National Lab and for making MG-RAST happen and for all their support) , and PhymmBL and GreenGenes for taxonomic analysis. The gut transcriptome data were already available, as part of a previous study. Our next step was to look for correlations between the distribution of bacterial phyla in the babies, and whether the type of bacteria they had in their guts had anything to do with their diet.

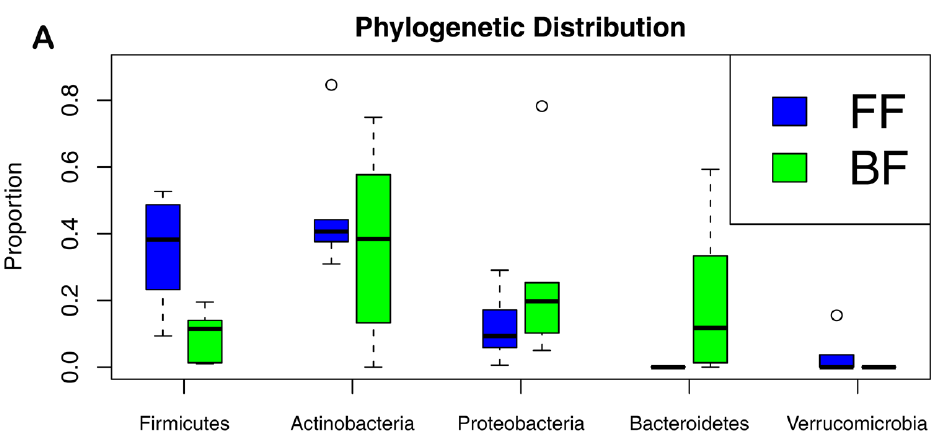

So here is what we found. First, most breastfed babies had a greater variety of bacterial phyla between them than formula-fed babies. Probably because the formula babies were all fed the same diet, whereas breastmilk composition varies between women. Second, the breastfed babies were richer in gram negative bacteria. Those are bacteria with a thin cell wall, a double cell membrane, and which have certain features that the gram positives (thick cell wall, single membrane) do not have. Also, almost all breastfed babies had a richer gut ecosystem.

Firmicutes and Actinobacteria are gram+; Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes are gram-. FF-formula fed babies, BF-breastfed babies. Genome Biology 2012, 13:R32 doi:10.1186/gb-2012-13-4-r32

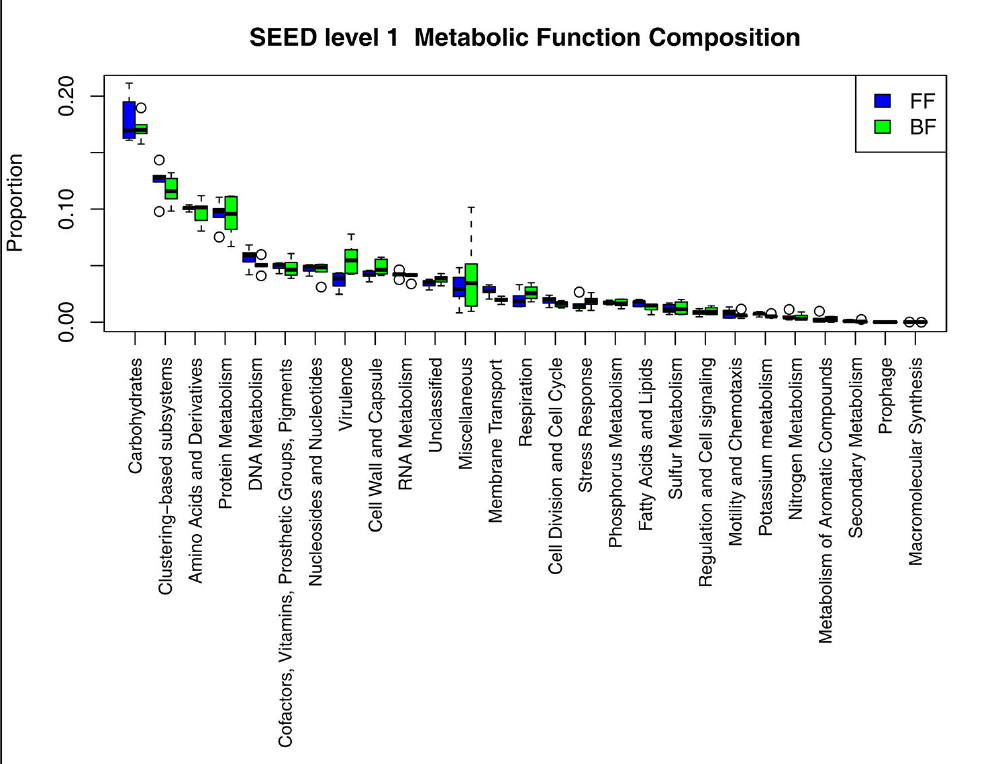

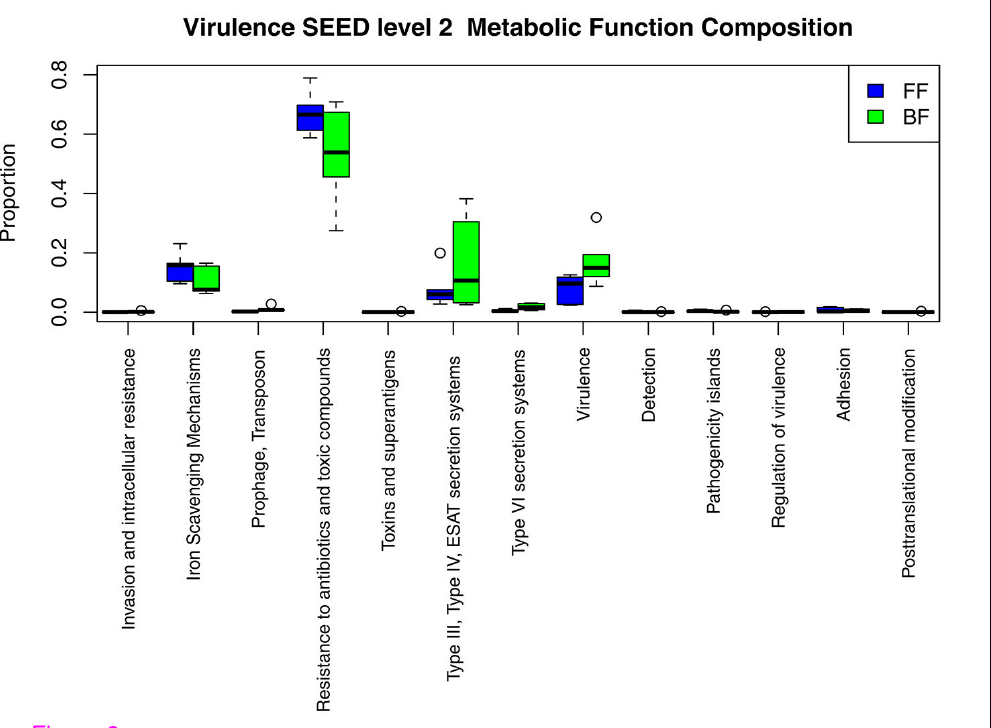

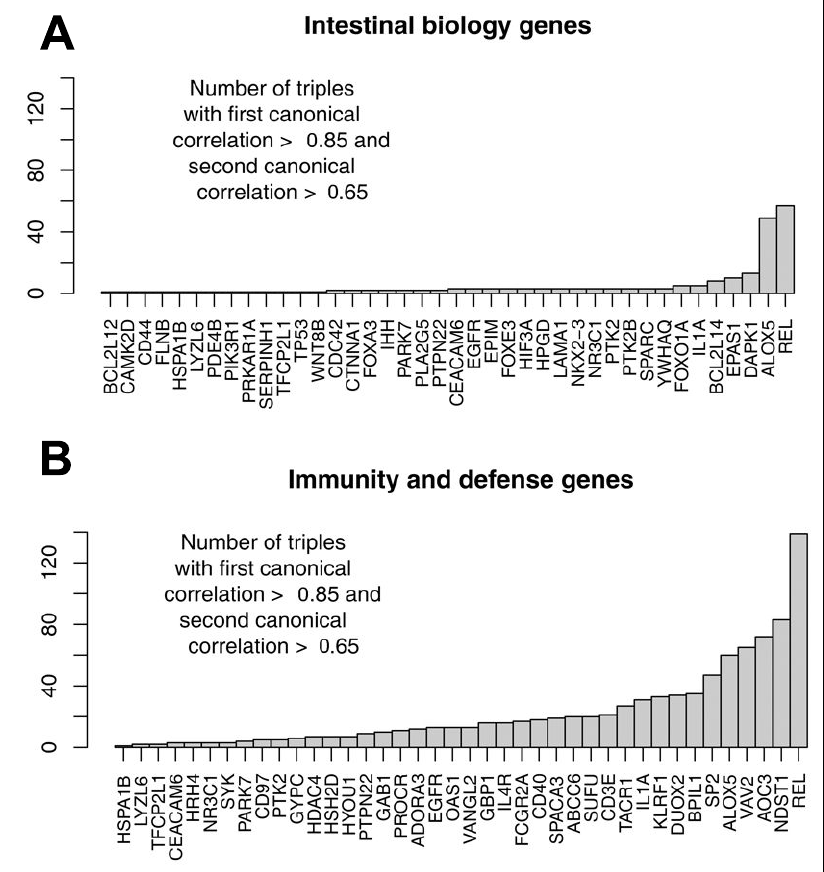

We then moved on to look at the genetic potential of the gut microbiome: how do the microbial communities differ between the breastfed and bottle-fed babies in terms of what they can do. The strongest difference between breastfed babies and bottle-fed babies was in the presence of virulence genes, and mostly those typical of gram-negatives: Type III & IV secretion systems. There were other differences, such as in carbohydrate processing enzymes. But the kicker was that the differences in the frequency of virulence genes in the microbiome also correlated well with the expression of immunity related-genes in the infant gut epithelial cells.

We observed the following: 1. Certain gram negative bacteria are dominant in the breastfed babies. 2. We saw that bacterial genes having to do with virulence were more abundant in the bacterial communities of breastfed babies 3. When looking closely at those genes, we saw that most of them were the virulence factors typical of gram negative bacteria (OK, not surprising given point[2] above, but a good verification). 4. At the same time, the breastfed babies expressed genes that had to do with immunity in their gut lining (epithelial) cells. The presence of virulence genes, and the expression of immunity genes in the gut epithelium correlated quite strongly (see B, below).

Taken together, this tells us that the following scenario may apply: mother’s milk tends to enrich certain types of gram negative bacteria, and those, in turn, stimulate the babies’ immune system. It’s as if the mother’s milk is setting up an immunity boot camp for the breastfed babies.

We got all sorts of feedback and even a bit of media coverage on this study. I was really happy when this study hit Reddit. Reddit is an aggregation site where anyone can submit any kind of story, and the “redditors” vote it up or down. Highly voted submissions are more visible, and get discussed more on the site. Generally, having a submission receive many “upvotes”, in Reddit parlance, shows an interest. (Well, the highest upvotes tend to go to pictures of funny kittens, but still.) The story made it to the top of the r/science category (also known as “subreddit”) with over 1300 upvotes . I logged in using my real name, and referred people to another subreddit, called IAmA (“I am a…”). In this case “I am a scientist who worked on this study, ask me anything“. There were quite a few questions, and it was a very interesting engagement with people about this work. Hopefully, good PR 🙂 and science communication.

Schwartz, S., Friedberg, I., Ivanov, I., Davidson, L., Goldsby, J., Dahl, D., Herman, D., Wang, M., Donovan, S., & Chapkin, R. (2012). A metagenomic study of diet-dependent interaction between gut microbiota and host in infants reveals differences in immune response Genome Biology, 13 (4) DOI: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-4-r32

> Taken together, this tells us that the following scenario may apply:

> mother’s milk tends to enrich certain types of gram negative bacteria,

> and those, in turn, stimulate the babies’ immune system. It’s as if the

> mother’s milk is setting up an immunity boot camp for the breastfed

> babies

Hmm, to me that seems somewhat biased towards an assumption that the process you’re observing is good.

I agree, from what you say (I’m not a biologist) it sounds like the babys immune system is being used in the BM case – but is that good? Does it have any good end effect (or should I say is that the cause of the beleived good effect of BM) – or is it just the baby having to fight off some bugs?

Dave

Another possibility is that the pathogenic genes identified are not (or not all) T3SS proteins, but homologous proteins that construct the flagella. Thus, these babies do not have low number of pathogens, but gram negative non-pathogens which have flagella (locomotory complexes). Flagella and T3SS are constructed from homologous proteins, and it is likely that MG-RAST may have identified some flagella genes as the T3SS. Flagellin (a major component in flagelle) is a well-known activator of innate immune system, specifically of a receptor called TLR-5 (toll-like receptor 5).