Book: Thirteen / Black Man. Richard K. Morgan

To say that Thirteen is a futuristic Chandlerian hardboiled-detective-fiction meets Gibson cyberpunk in a Swiftian satire of contemporary USA would be a cumbersomely loaded one-liner describing a no less loaded but sleekly streamlined novel. Saying that would also do injustice to Gibson, Chandler, Swift, the English language and especially Richard Morgan.

This book has it all, and then some. Frame-by-frame violence? Check. Cool tech including AIs of different flavors, weapons, and assorted plug-in-your-CNS-and-get-groovy? Check. Biotechnology that includes genetically enhanced soldiers practicing a Martian martial art and shooting virus laced bullets? Check. An uneasy, sexually-charged partnership between a lady cop who plays by the rules and a bounty hunter who doesn’t? Check. Political statements about the current US through a futuristic caricature thereof? Check.

Carl Marsalis is a “variant Thirteen”, a modified human raised in a crèche with his peers to become a lone-wolf, high aggression, low sociability fighter. Thirteens’ genomes were designed to resuscitate the primitive human male that existed during hunter-gatherer times, when alpha males ruled, and sociopathy combined with aggression had their survival merits. In other words, Marsalis is a throwback to a time when Men were Men, something the 22nd century society cannot handle. But the same society that cannot handle such men is still fighting wars in remote places, and how would a government raise an army from a pool of girlie-men? The answer: use genetic engineering to create a Yujimbo, a Conan, a Tarzan, a Universal Soldier, a Mad Max, a John Carter, or a Dirty Harry: take your pick. all those Real Men who get out, get the job done, don’t ask questions and don’t give a shit about what the rest of us think about them. Make enough of those to fight your remote wars in Central Asia and South America, and you can keep the rest of the cudlips (a derogatory terms used by Thirteens to allude to humans as herd animals) happy and carefree.

Carl Marsalis is a “variant Thirteen”, a modified human raised in a crèche with his peers to become a lone-wolf, high aggression, low sociability fighter. Thirteens’ genomes were designed to resuscitate the primitive human male that existed during hunter-gatherer times, when alpha males ruled, and sociopathy combined with aggression had their survival merits. In other words, Marsalis is a throwback to a time when Men were Men, something the 22nd century society cannot handle. But the same society that cannot handle such men is still fighting wars in remote places, and how would a government raise an army from a pool of girlie-men? The answer: use genetic engineering to create a Yujimbo, a Conan, a Tarzan, a Universal Soldier, a Mad Max, a John Carter, or a Dirty Harry: take your pick. all those Real Men who get out, get the job done, don’t ask questions and don’t give a shit about what the rest of us think about them. Make enough of those to fight your remote wars in Central Asia and South America, and you can keep the rest of the cudlips (a derogatory terms used by Thirteens to allude to humans as herd animals) happy and carefree.

“We’re not like you. We’re the Witches. We’re the violent exiles, the lone-wolf nomads that you bred out of the race back when growing crops and living in one place became so popular. We don’t have, and we don’t need a social context.”

As usual, those plans backfire, and Thirteens are deemed too dangerous to keep on Earth. In response to humanity’s xenophobic backlash to the “twists”, the pejorative term for Thirteens, Earth’s governments exile them to Mars. Mars is a terraformed New New World resembling the early Australia or America: somewhere to send the social misfits, never mind that society itself created them. But Marsalis wins a return-to-Earth lottery and gets a ticket back to Earth. He is tolerated as long as he keeps his genetic identity secret, since it is not legal for Thirteens to walk free. Another condition is that he works as a bounty hunter for UNGLA, the United Nations Genetic Legislation Authority. Apparently not all Thirteens have gone willingly to Mars, and Marsalis is the one who tracks them down and kills them. The book opens with such an execution, and some “collateral damage”. Marsalis’s almost blase attitude towards the value of life offends us until quite quickly we realize that many non-engineered humans are much worse morally than he is.

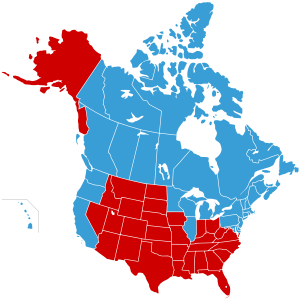

Richard Morgan has also decided to take current US political partisanship to the extreme, and divide the US into three countries. Remember the Jesusland maps that were circulating on the Internet after Bush’s second election? Morgan uses those maps to outline future America. The secessionist Pacific Rim (RimSec) which is pretty much modern-day California, with its perceived cultural openness, innovation-driven boom-bust supercapitalist economy allied with the strong  economies of Asia. This is contrasted with The Republic or Jesusland. Oppressively religious, with a failed education system and failing agrarian economy, the fundamentalist-run Jesusland is a Bible-Belt pastiche. Finally, The Northeastern states are dominated by the UN, and heavily aligned with a culturally-tolerant, socialistic Europe. A strong endorsement of Morgan’s futuristic vision is the title under which his book was distributed in the US. The original title, Black Man was deemed offensive by the US publishers, and was changed by them to Thirteen. Jesusland would probably have banned the book altogether: graphic sex, violence, drugs, profanity and general apostasy and heresy.

economies of Asia. This is contrasted with The Republic or Jesusland. Oppressively religious, with a failed education system and failing agrarian economy, the fundamentalist-run Jesusland is a Bible-Belt pastiche. Finally, The Northeastern states are dominated by the UN, and heavily aligned with a culturally-tolerant, socialistic Europe. A strong endorsement of Morgan’s futuristic vision is the title under which his book was distributed in the US. The original title, Black Man was deemed offensive by the US publishers, and was changed by them to Thirteen. Jesusland would probably have banned the book altogether: graphic sex, violence, drugs, profanity and general apostasy and heresy.

“To be a believer, you … have to want something big and patriarchial around to take care of business for you. You have to be apt for worship, and Thirteens don’t do worship, of anyone or anything”.

Marsalis is black and a Thirteen. Twenty-first Century racial prejudice meets the 22nd Century genetic one, as one Jesusland officer called him the “nigger twist”. This is played upon a lot in the book. Perhaps a bit too much.

After Marsalis completes a UNGLA-sanctioned murder mission of another Thirteen in South America, he gets arrested in a police entrapment in Jesusland during a layover on his flight home to London. He is sprung from jail by COLIN, the UN COLonial INitiative authority from the Northeastern states, to track down a renegade Thirteen who also came back from Mars and is going through a killing spree throughout North America. The victims are purposefully targeted, yet how they are connected is a mystery. As usual in hardboiled fiction, the arduous and twisted (pun intended?) detection trail slowly leads to reveal corruption in the upper echelons. The rotten firmaments of civilized society are exposed as being run by people even more sociopathic and dangerous than the elusive and murderous Thirteen Marsalis is tracking. When Marsalis finally figures things out and goes on his own revenge spree, we cannot help but cheer. That is about all of the plot I should probably reveal.

Interestingly, as we go through the book Marsalis is slowly revealed as the antithesis to what a Thirteen is supposed to be. Marsalis holds his aggression in check better than most cudlips. He follows society’s norms (although, as the text repeatedly states, only because he is smart enough to stay out of trouble, not because he accepts them). He is cool, calculated, and even when following his gut feeling he seems more cerebral than  his human partners. We learn that a cold-blooded killer is more humane than a hot-blooded one. Twists may kill, but cudlips massacre. The reason lies with the particular brand of sociopathy wired into Thirteens: their disinterest in society and social norms defuses the aspiration for power over others that some humans have. A Thirteen would never climb the corporate ladder, run for political office, impose his religion over others, or decide to conquer the world: he has no interest. Speaking of religion, see the quote above. Thirteens are wired to be atheists.

his human partners. We learn that a cold-blooded killer is more humane than a hot-blooded one. Twists may kill, but cudlips massacre. The reason lies with the particular brand of sociopathy wired into Thirteens: their disinterest in society and social norms defuses the aspiration for power over others that some humans have. A Thirteen would never climb the corporate ladder, run for political office, impose his religion over others, or decide to conquer the world: he has no interest. Speaking of religion, see the quote above. Thirteens are wired to be atheists.

Not aspiring to a position of power, not wanting to shepherd the flock, means a Thirteen will not do the damage that it takes to get that position, or to hold it.

“Warlord wants the same thing any cudlip politician wants — legitimacy, recognition, and respect from the rest of the herd. The whole nine-car motorcade.”

Morgan paints a mixed picture of humanity: collaborative societies accomplish things. They grow corn, build cities, cure diseases and colonize Mars. But in a collaborative society, it is mostly the power-hungry sociopaths that make it to the top, or to a top. Humanity’s accomplished all its good things by working together, and deferring to authority while doing so. The price we pay for working together, is having someone work us, and that someone may not have the Greater Good in their minds. The Thirteen can look at us from the sidelines, and expose our leaders for what they are, but at the end of the day:

“They (cudlips) won because it worked. Group cooperation and bowing down to some thug with a beard worked better than standing alone as a thirteen was ever going to…they hunted us down, they exterminated us, and they got the future as the prize.”

I concur – an enjoyable read.